Do you remember how you first learned about object-oriented software design? How they teach it at University?

You probably looked at objects from the real world and their is-a or extends relationships. A circle is-a shape, and it extends shape. A cat is-an animal, and it extends animal.

Today I want to re-visit this kind of approach to learning object-oriented design and discuss it’s advantages and shortcomings.

Intro (TL;DR)

My name is David and in this video series, I am talking about things you can do to become a better software developer.

I’ve been working as a freelance developer, technical coach and trainer for some time now. I am helping my clients - among other things - to handle their legacy code bases better.

And many problems I see in those legacy code bases are caused by not putting enough emphasis on software design. By taking a simplistic approach, almost as simplistic as the one described before.

Like, find the nouns and verbs in the specification and that’s basically the design.

So, when we talk about software design in the workshops I teach, I also spend some time trying to show people that the “first-gut-feeling” approach to design does not work.

Because when you know why and how this approach does not work, you will understand the techniques you need to learn more easily.

Question / Problem

Some software designs look like someone searched for nouns and verbs in the specification (or the business domain). Then they made classes directly from the nouns and methods from the verbs.

And designs like that seem right at the first glance, because they model the objects from “the real world”.

But then you run into problems. Writing tests is hard. There are a few classes that are huge and do all the work, and other classes that barely do anything at all. There are big domain objects that contain 15, 20 or more fields.

There are services that depend on services that depend on services - many layers down the onion - even though all of them are stateless.

There are classes that have many dependencies which contributes to your testability problem.

The design is neither extensible nor portable. You cannot re-use the business logic in a slightly different situation because of technical limitations. Adding additional features requires you to change many pieces of code in many different locations.

And all of that slows you down. Every. Time. You. Want. To. Change. Something.

What happened here? Well, the “objects from the real world” approach to software design almost inevitably leads to bad design.

Let me give you a little example.

Solution

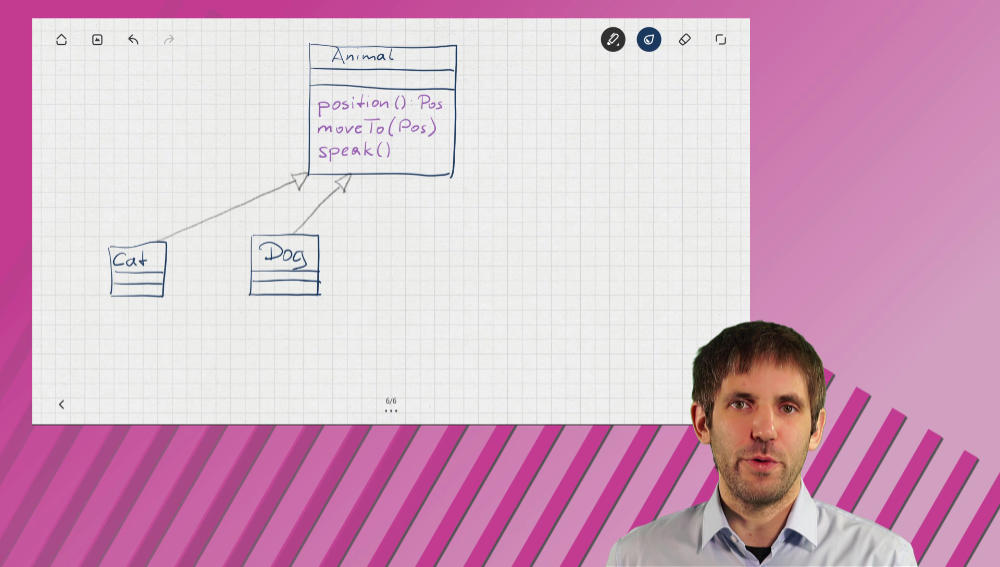

I want to design a very simple class hierarchy with you. There are Cats and Dogs, and both of them are Animals. An Animal has a position and we can tell it to move to another position.

Animals also have a method speak. When we call this method on an object of type Cat it would output “meow”, when we call it on a Dog it would output “woof”.

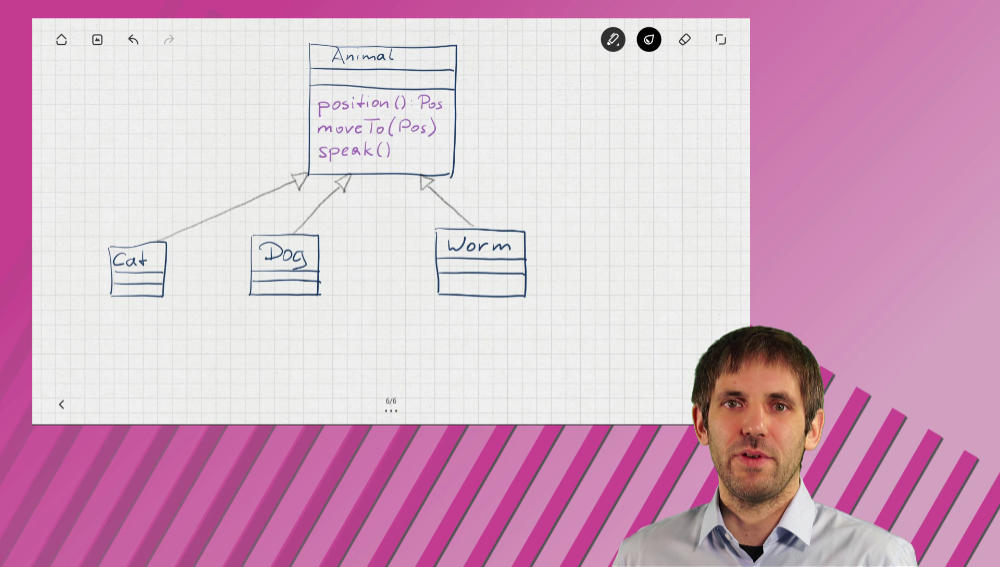

But now we got new requirements and we need a new class Worm. “Easy”, we think, it’s also an animal.

But how do we implement “speak” here?

All right, leave it empty. Worms don’t speak. That’s not really nice, because even calling “speak” does not make sense on a worm.

But we can live with that. There is not much harm in leaving a method empty. Right?

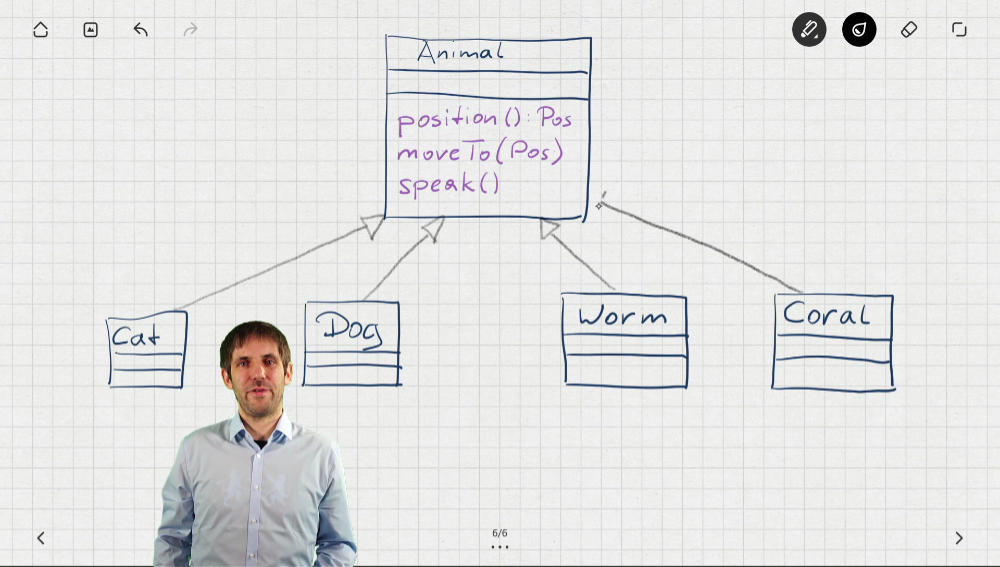

Wait, we got new requirements again. And we need another class to support them. We need a Coral.

Now, corals do not speak too, but they also do not move.

We have the same problem as before, but slightly worse: How can we implement moveTo here?

Think about it for a moment… I think in this class hierarchy, there are only two reasonable ways to implement moveTo: Do nothing or raise an error (like, throw an Exception).

What if we did nothing? A programmer would never call moveTo on a Coral, right?

Maybe they wouldn’t, but they might not know that what they have is a Coral. They get an Animal object, call moveTo, at some point later in time call getPosition - and the animal would still be at its old position.

That would be surprising to the programmer. I am almost certain that they would fire up the debugger to find out what’s going on here. This behaviour violates the “Principle of Least Surprise”.

So, it’s “raise an error”, right? Well, not so fast…

Suppose there is some code that iterates over all animals and moves them. This code now does not work anymore.

By adding the coral class the way we did it - By raising an error in a situation that is perfectly fine from the caller’s perspective - We broke some totally unrelated code.

How can adding new code break existing code?

It was possible because we violated the “Liskov Substitution Principle”: We wrote a class that, for some calling function, is not compatible with its base class.

Conclusion

How can we add the coral class without causing any problems? We cannot - because this is the wrong question.

We cannot do it because looking at the “static structure” of the “real world” and creating a software design from it does not work. At least it does not work in most cases.

The objects and relationships we - humans - see are often not the objects and relationships our software is interested in.

In software, we try to implement some behaviour. We want to make computers do something. In order to do that, we must understand and model behaviours from the real world.

And we must take care to only model the behaviours and objects our software needs to do its job. Whenever we model less or more, we make our design needlessly complicated.

The simplistic object oriented design we learn at school - “Cat is-an Animal” or “Car has tires” - is useful for learning to think in objects. But it is not necessarily useful for creating real software systems.

We must do more in order to model those real software systems. We must think about coupling and cohesion. Follow software design principles. Know about design patterns. Know the rules so well that we know when to follow them and when to break them.

But those are topics for upcoming videos. Today I wanted to show you how a too simplistic design can fall short pretty quickly.

CTA

How do you and your team design your software? Do you have a process? Does your design look like “nouns+verbs” or is it more sophisticated?

Did you already experience situations where a design that looked absolutely reasonable stopped working because of new requirements? What are you planning to do next?

Tell me in the comments or on Twitter - I am @dtanzer there. And do not forget to subscribe to this channel, so you do not miss any updates!