Did you ever hear phrases like “Agile is not faster” or “You need to do un-intuitive things to become agile”? Did that make sense to you?

To me, in the beginning, those phrases made no sense at all. But now I think that they are the main reason why so many companies do not get “agile” right. They “do” agile only to become faster. But they do not “get” some of the most important underlying principles.

Today, I want to talk about a very important but also un-intuitive principle: You must slow down to move fast.

Intro (TL;DR)

My name is David and in this video series, I will talk about things you can do to become a better software developer.

I am a freelance consultant and coach - and in the last 12 years I have strived to constantly learn and improve my skills as a software developer, architect, and also as a tester, team coach and trainer.

Many of the things I learned - like today’s topic - were hard to grasp for me. Because some of things we have to do to become better make no sense at all. Until you think hard about them and try them and learn more - And suddenly, those things are perfectly reasonable and the opposite does not make sense anymore.

For example, “Slow down to move faster”.

Today, I want to talk about how agile software development is not “fast”. And how it can still be worthwhile, because it enables you to deliver more value in less time.

Which means that it is faster, although it is slower. Confused? Me too. Let me start again, this time a little bit slower.

Question / Problem

Many things we do in agile software development seem to be slower than in a “traditional project”.

We are doing some planning, some design, some architecture in every iteration. We even change our design and architecture on a regular basis. This definitely adds some overhead.

We take more care when writing code. We write a lot of tests. We run them often. We re-think our design decisions after every green test and refactor often.

We spend a lot of time automating things and testing that automation. We automate user acceptance testing, performance testing, regression testing, deployments and even releases to production.

We work in pairs or even in small groups. Five people working togehter, on the same feature, even the same line of code? That cannot be faster than 5 people working in parallel, not getting in the way of each other.

And yet, often it is.

How can that possibly be true? How can slowing down make us faster?

Solution

Let’s look at two teams. Team “Niagara” works in a waterfall-style, plan-then-do-then-integrate, command-and-control way. People do exactly what they are told or what was written down in the plan.

Team “Gazelle” is more agile. The team experiments a lot, they try to get good feedback early, they release often and take care to do things right and to automate everything.

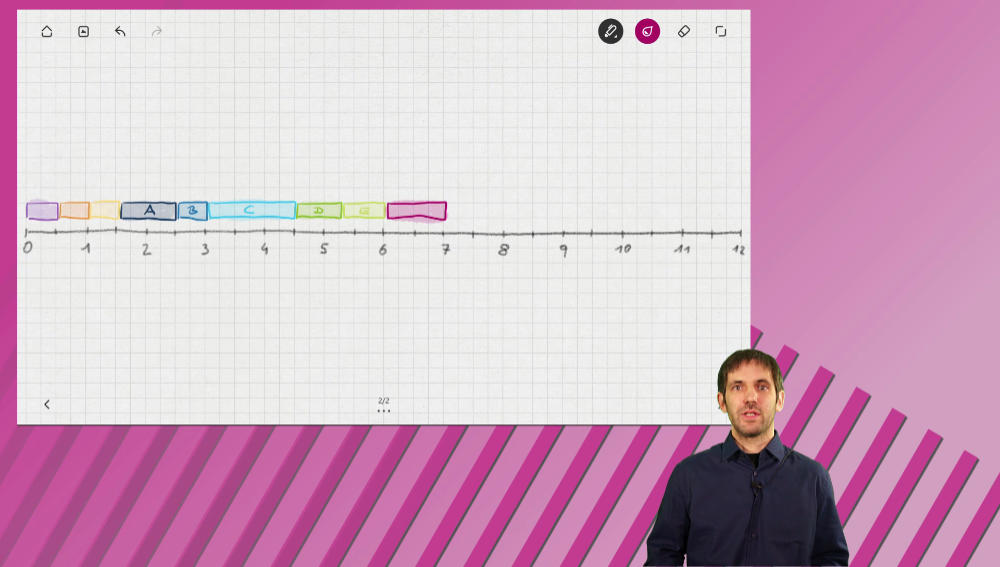

We ask both teams to deliver 5 features for us: A, B, C, D and E.

Team Niagara first plans the project, then they sketch out their software architecture. They do some project preparation work, like setting up their repositories, build systems, CI server, IDEs and so on.

Then they start to implement the features. First feature A, then B, C, D and E. They integrate and test everything. Things went more or less as planned, so they release to their users.

It took them 7 weeks.

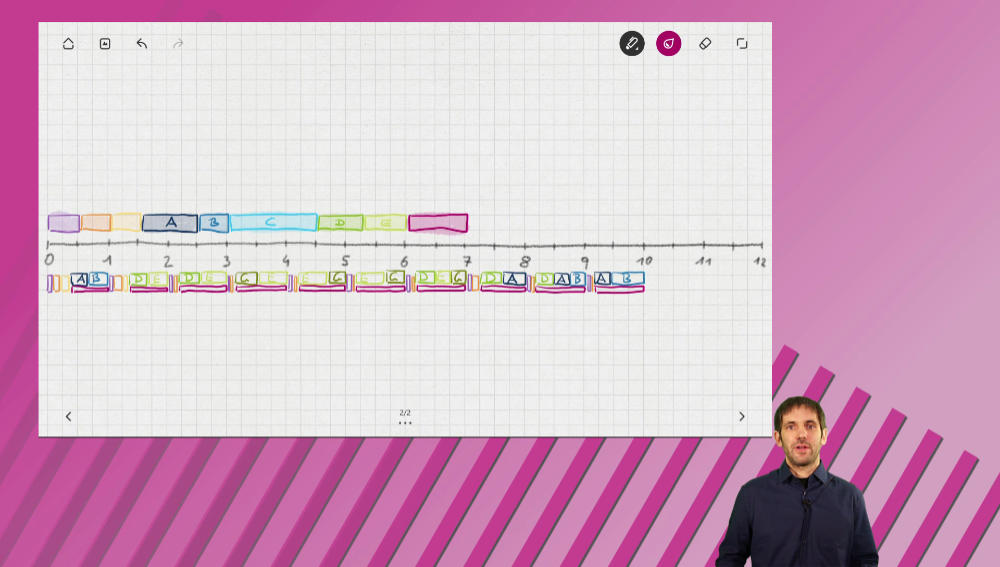

Team Gazelle, on the other hand, start with a little bit of project planning, software architecture and preparation work. Then they implement a very basic version of Features A and B and they integrate and test all the time. After a week, they release what they have to real users.

Users cannot really use the software productively yet, but they give feedback. And from that feedback, the team learns that users, right now, really need D and E.

So, the team works on D and E next, but they also have to do some project planning, preparation work and software architecture. A week later, they release again.

The users try it, and they like D and E, but they would need a more elaborate version of those two features to use them productively. The team listens to their feedback, and they work even more on D and E.

Also, during that week, users report some defects - they seem to be really trying the software! - so the team fixes those right away.

During the next review, where the team gathers feedback from other stakeholders, some “friendly” users agree to use the software in production now, since it has enough features to provide at least some value.

Also, a user suggests that a feature G would be awesome. And, someone from operations brings some usage statistics and they suggest that the current implementation of feature E will not scale.

Now the team addresses those issues. They completely re-do E and start with G. They fix defects and make some minor corrections to D. A week later, they release again.

And this cycle of implementation, release, feedback and re-planning continues until, after 10 weeks, they are done.

So, delivering the software took longer with the agile approach, and the team did not even deliver feature C at all! Was that really better?

Well, the story does not end here. With software, it never ends after the release.

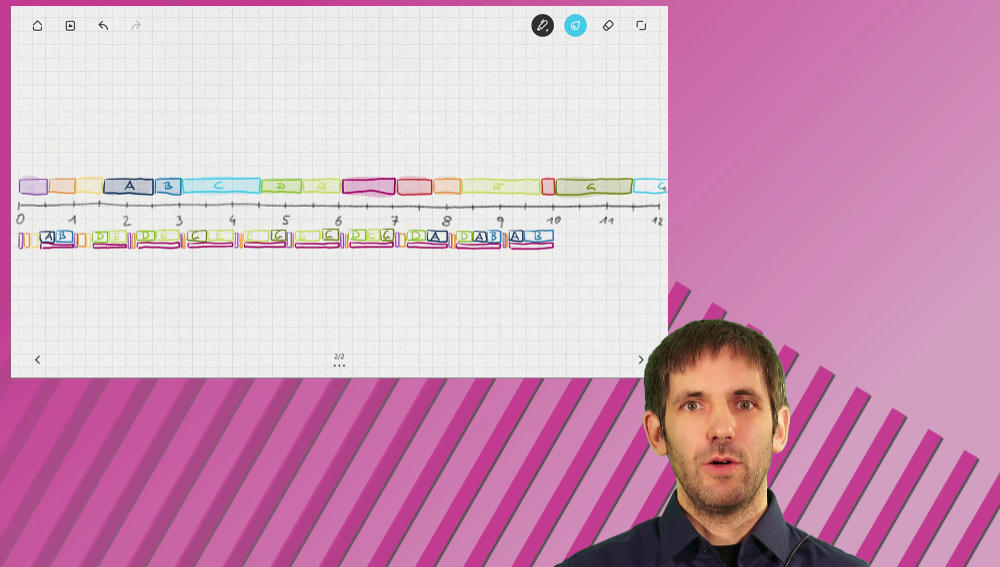

Right after the rollout, team Niagara gets the first phone calls. The software does not scale. They have major slowdowns and production outages.

They have to work night-shifts to prepare a quick fix, and then work even more to create the real solution to the scaling problem. They have to re-architect feature E, which causes the problems. But some design that is in place for feature C makes re-doing E harder, so it takes even longer than at the first time.

While they work on that, bug reports keep rolling in, so the team starts fixing those.

And people complain that the software does not really help them to do their job, because some major parts at the beginning of all workflows are missing. Management decides that the team needs to implement feature G.

But because all that code in place - The fixes for E, all the other features and the hastily-done bugfixes, implementing feature G takes quite long.

After the next hotfix release, the team analyzes some metrics. They realize that only a tiny percentage of the users uses feature C. To make future maintenance easier, they decide to remove a part of C.

While team Niagara did all that, team Gazelle moved on to the next piece of work, for another application. In parallel, they fixed some minor defects and collected feature requests for the next major release.

Conclusion

In the end, they delivered faster and cheaper, they are now ready to start working on the next major release and they were able to provide value in another application while they had some slack.

One could say that team Niagara made mistakes during requirements engineering and software architecture. They should have forseen those things that made them slower in the end!

But there will always be unforseen things. Even the best requirements engineer or software architect cannot anticipate everything that could ever happen.

So, by getting feedback early, being able to react quickly and working hard to have high quality code, design and architecture, the “agile” team was faster.

CTA

In a future episode, I want to talk in more detail about some aspects of this example. And I will try to answer your questions. So ask them right here in the comments or ping me on Twitter - I am @dtanzer there.

And subscribe to this channel so you don’t miss any updates!